“Hell cannot be so terrible”

Verdun. For a past generation, this one simple word evoked all the horror of war. Displacement, destruction, devastation, death. Hyperbole is not even possible when describing the events of the Battle of Verdun.

Verdun is a town that found itself on the eastern frontier of France in 1914 – right on the border with Germany. A natural gateway to Paris, it was heavily fortified as a defensive measure against a German invasion. However, when the Germans did strike in 1916, most of the French troops had been moved to other fronts. A huge convoy of men and munitions began – the French command wanted Verdun kept at all costs.

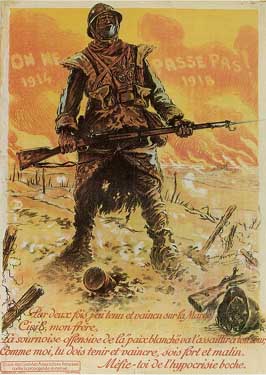

“On ne passe pas!” (They shall not pass) was the oft quoted battle cry, coined by French General Robert Neville.

French military poster with the words “On ne passe pas!” (They shall not pass)

From the 21st of February to the 18th of December, 1916, unrelenting warfare was carried out across the forested hills and farms outside of the evacuated, destroyed town of Verdun. The numbers alone are shocking :

9 months, 3 weeks and 6 days of continuous fighting

Over 377,000 casualties on the French side

Over 337,000 on the German side

Over 70 000 casualties per month – just on this one battlefield

Over 40 million artillery shells fired

The battle for Verdun turned the beautiful French countryside into an alien landscape – the forests were obliterated, the farms were pockmarked with huge shell craters, and the 9 rural villages that surrounded Verdun were erased – nothing was left. Imagine these villages, home to generations of farmers and craftspeople, bakers and priests, going back to medieval times. Gone. Their former happy streets became places of unimaginable horror. The ground, churned up, a muddy, murky mess of clay, shells, and human remains.

French troops in the muck and mire

German machine gunners wearing gas masks in case of chemical attack

This was Verdun. A new type of warfare was being waged here. Each side dug in, building trenches several hundred metres away from the other side. A constant barrage of artillery rained down on the soldiers on either side. Each day the men would leave the trenches to fight in “no mans’ land”, almost certain death. Reinforcements would be brought in, and this cycle would play out over and over again. Territory was gained and lost in metres. By the end of the battle, both sides were essentially in the same place they were at the beginning. This was a war of attrition. German Chief of General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, famously stated that he wanted to “bleed France white”. In other words, rather than gain territory as was the traditional goal of a battle, he wanted to eliminate so many of France’s infantry that they would have to surrender. His strategy nearly worked, but as the numbers show, it was just as devastating to the German forces as it was to the French. To call Verdun a victory for either side would be incorrect – Verdun was a victory for death alone.

A wounded French soldier lives to fight another day

Today the town of Verdun has been rebuilt. But none of the 9 rural villages have been. They were the site of too great a tragedy for people to return and rebuild. The church of the village Fleury was rebuilt after the war, but the people did not return. Visiting Fleury is a haunting reminder of the past – the former streets are marked by small concrete pillars – indicating where this family or that family lived, where the baker practiced his craft, where the blacksmith forged the farmers’ tools. The ground is still cratered, but trees and grass grow once again on this former moonscape.

A cafe and grocery store once stood on this spot.

The cratered landscape sprouts life once again. There are still off-limits areas around the battlefield because of live shells in the ground.

Up the road from Fleury is the Verdun Memorial Museum. This is an excellent museum that does not glorify war in any way. Nor does it stand as a monument to any sort of French nationalism. The French flag flies beside the German flag here, with the European Union flag in between. The equipment and uniforms will sate the most dedicated military history buff, while the personal stories and the excellent film shown in the theatre will make those human connections that are so important in a memorial like this.

The Verdun Memorial Museum

Down the road from Fleury, at the head of a French military cemetery is the huge Douaumont Ossuary – filled with the remains of more than 130 000 unidentified dead. The decision was made at the conclusion of the war to inter all the remains together – identification by nationality was all but impossible for many of the bodies, but more importantly, irrelevant. Each one was a son, possibly a brother, possibly a husband, possibly a father. Each one came to Verdun to do “his duty” for his nation, and in so doing, lost his life.

The Douaumont Ossuary at the head of the French military cemetery. The bottom of the ossuary is filled with the remains of the unidentified bodies on the battlefield. One of the bodies was transported to Paris and lies under the Arc de Triomphe at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

One of those men, a French lieutenant,, wrote in his journal, “Humanity is mad. It must be mad to do what it is doing. What a massacre! What scenes of horror and carnage! I cannot find words to translate my impressions. Hell cannot be so terrible.” He was later killed in an artillery attack.

The battlefields of Verdun are tranquil now. Very peaceful. And the survivors of this battle are all gone. Soon, anyone who was alive during WW I will be gone. But the Douaumont Ossuary, the church at Fleury, and the Verdun Memorial museum remain to remind us: never forget, and never repeat.

Verdun, once a site of savage warfare, now a symbol of reconciliation and peace for the nations of France and Germany.

Recent Comments