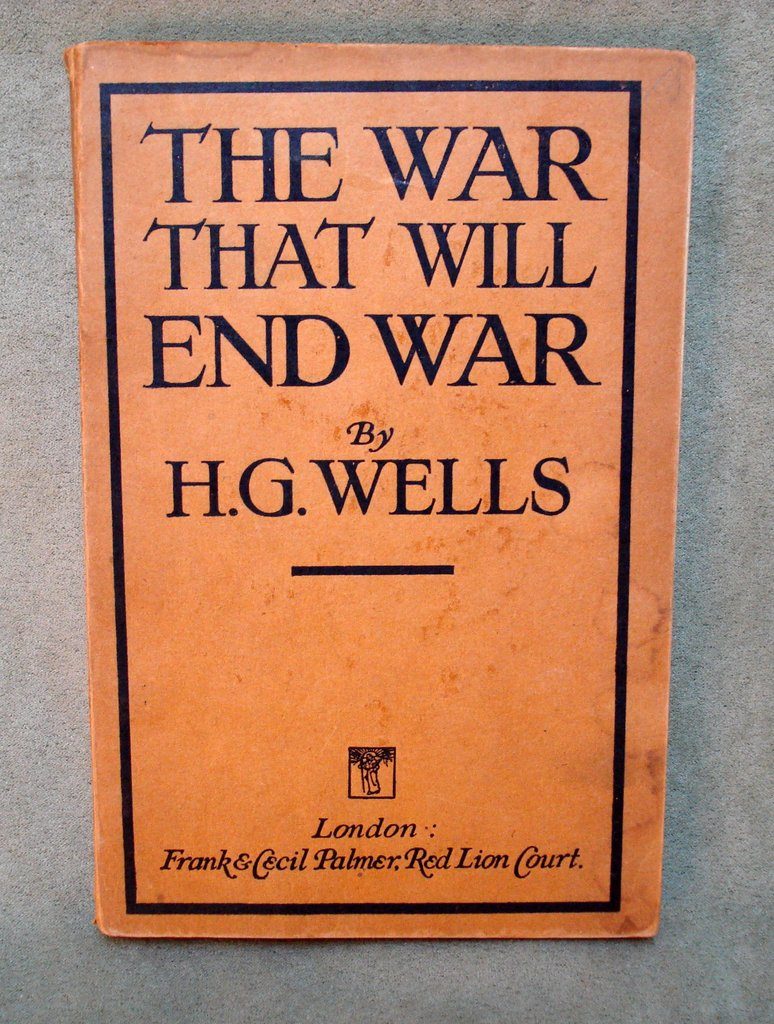

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, British author H.G. Wells wrote a series of essays that were published as “The War That Will End War.” The ferocity of the battles that ensued, and the pure destructive power of the new battlefield technologies cemented this idea in the public conscience – after WWI, the powers that be would no longer have any appetite for warfare. So much for that notion – it was a mere 20 years later that Germany invaded Poland, starting the Second World War.

The First World War has no surviving veterans – I was in Paris when the last French WWI vet Lazare Ponticelli died in March 2008. Flags were at half mast all over the city – of all the countries in Europe, France was more devastated than any other by the First World War – the scars run deep. I remember as a child in the 1970’s that there were several WWI veterans on my paper route in North Vancouver – several that I knew of anyway. They were the ones missing a leg, or both legs, or an arm. Some of them would visit our elementary school for our Remembrance Day assemblies, and we would see them at the cenotaph on November 11. I knew I was to respect them, and that I was to be thankful for their service. In my child’s mind, in my comfortable home, in my peaceful country, I couldn’t really fathom what their service entailed.

Canadian troops go “over the top” at Vimy Ridge

As a teacher and a tour guide, I have visited World War I sites throughout Europe, mostly in France and Belgium. Though I certainly have no claim to understanding the experiences of the soldiers in that war, these pilgrimages have helped me to better recognize and respect them. The battlefields, museums, and monuments at Verdun in Eastern France, Vimy Ridge in Northern France, and Ypres in Belgium are solemn places where we can reflect on the sacrifices of past generations. They do not glorify war, nor do they celebrate the victory of one side over another – instead they bring us into the experiences of ordinary people thrown into extraordinary circumstances – they put human faces on the statistics, and they implore us not to make the same mistakes again.

German soldiers and their mule all sporting gas masks as they prepare to go into battle at Verdun.

Of all these sites, the In Flanders Fields museum in Ypres personalizes the First World War in a profound way, bringing the events of 100 years ago to the present generation. When you enter the museum, you are given a small wristband which you use to sign in – it gives you the identity of a real person from the war era – soldier, nurse, farmer, etc. – and you take that identity with you through the interactive displays, finding out how that person’s life was affected by the war as it raged from 1914 to 1918. Through a combination of relics from the war and modern technology, the In Flanders Fields museum has succeeded in insuring this century old event will not be forgotten, at least not by those who visit. The most profound aspect of a visit here is the way that the personal stories are shared.

The medieval Ypres Cloth Hall – destroyed by relentless shelling in the First World War.

The Ypres Cloth Hall today – containing the excellent In Flanders Fields Museum.

Lazare Ponticelli, through his long life, often obliged when people asked him to share his personal story. As a boy of 16, Ponticelli signed up to fight the enemy of his newly adopted country (he was originally from Italy). He recalled that during extended periods of artillery fire, the young men waiting in the trenches would say to each other, “If I die, you’ll remember me, won’t you?”, as though their chief concern wasn’t their own impending doom, but the idea that they would be obliterated from history – forgotten. He seemed to understand that the men in the other trenches felt the same way. He recalled tripping over an injured German soldier in the dark, who then fully expected to be killed, but in a move of desperation, held up two fingers to Ponticelli, which he took to understand he had two children. Ponticelli did not pull the trigger, but took him prisoner instead. As a centenarian, he showed no interest in labelling anyone his enemy. He said he did not understand why on earth he, or they, had been fighting. “You shoot at men who are fathers. War is completely stupid.” Was H.G. Wells displaying some grand naiveté when he wrote “The War That Will End War”? Perhaps. Or maybe his thoughts were a call to future generations – a hope that eventually, we will learn something profound from the experiences of men like Lazare Ponticelli.

Lazare Ponticelli at age 106 – 90 years after he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion at the start of the First World War.

Craig, thank you so much for exposing me to the In Flanders Fields Museum. I learned so Much more about WWI than I ever knew before and that place, more than any other on our trip made the biggest impression on me ( yes more than Westvleteren and even going to Dachau ). I will go back there sometime because I need to spend a whole day there. I just need to. Thanks again man